Peer Recovery Support Services (PRSS) have emerged as a transformative element in the health care landscape. These services, provided by individuals with lived experience of recovery, offer personalized, empathetic support that enhances patient engagement in recovery and harm reduction efforts. PRSS foster a sense of community and provide ongoing mentorship, helping to improve individual health outcomes while alleviating the financial burden on health care systems by decreasing hospital readmissions, shortening in-patient lengths of stay, and minimizing the use of emergency departments. Overall, the integration of PRSS into care models represents a cost-effective strategy that promotes sustainable recovery and long-term health benefits for patients.

A literature review of articles demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of PRSS between 2020 and 2023, published in Community Mental Health Journal, found that “the majority of the studies identified were focused on healthcare cost-avoidance.” Some studies supported PRSS as a method of avoiding costly medical services, while others had mixed results. The scoping review revealed limited studies addressing cost savings associated with PRSS and deduced that further research on the economic impact of PRSS is warranted.

To learn more about the potential impact of PRSS on the total cost of health care, I connected with Alliance participant Sierra Castedo de Martell, Assistant Research Scientist with the JEAP Initiative at Chestnut Health Systems’ Lighthouse Institute. Dr. Castedo de Martell has been instrumental in researching the financial impact of PRSS on total cost of health care, culminating in the creation of a cost-effectiveness calculator for peer recovery support services and for bystander naloxone distribution and a forthcoming journal article reporting the results of a cost-effectiveness analysis of PRSS (Castedo de Martell et al., under review).

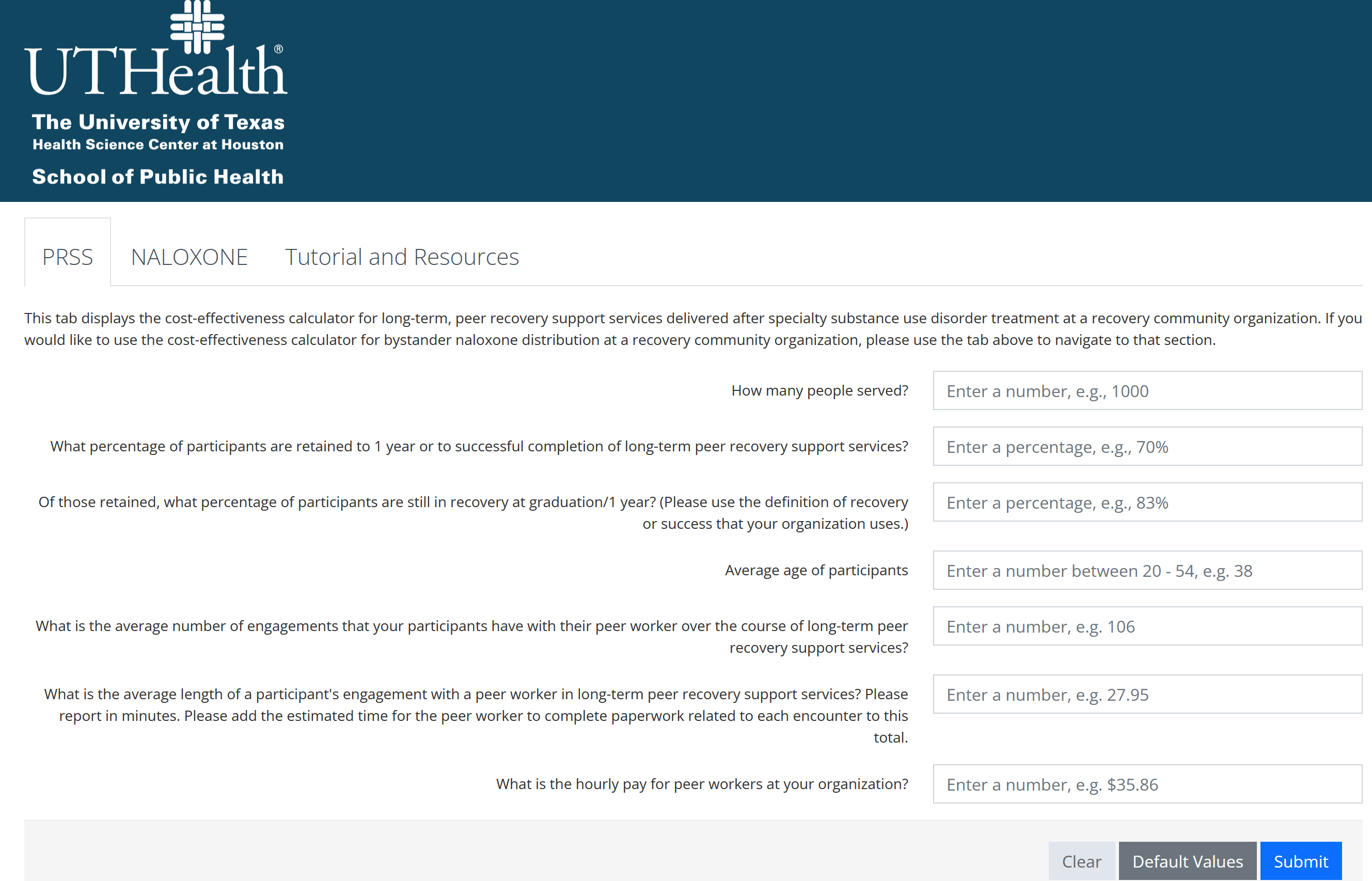

Cost-effectiveness calculator for peer recovery support services and for bystander naloxone distribution

Eric (Alliance for Addiction Payment Reform): Dr. Castedo de Martell, you have been forthcoming with the fact that you are a person in long-term recovery. In recognition of National Recovery Month, if you’re comfortable, would you be willing to share how your personal recovery journey has impacted the work you do on a daily basis?

Dr. Castedo de Martell (JEAP Initiative and Lighthouse Institute): I found recovery at the collegiate recovery program at the University of Texas at Austin at a time when there were very few collegiate recovery programs nationally – fewer than 30 the year I entered recovery (2012). That kind of combination of formal and informal peer support in my own normal environment was absolutely critical. I – of course – had the privilege to be in grad school at all, but I had extremely limited financial resources, and my insurance and income were all dependent on me continuing to be in grad school. Taking a medical leave from school would have meant losing all the income I had, my housing, and even my bus pass. But I didn’t have to leave school. I bypassed treatment completely because of the support I had at the collegiate recovery program, individual therapy at the school’s counseling center, and the support I got from the informal peer recovery community on and off campus. I later went on to serve as that collegiate recovery program’s director, and over the years, I continued to see just how rare that experience I had was, how patchy the system of care is, how expensive so much of it is, and how difficult it is to get help on demand for little or no money like I did. When I was director of the collegiate recovery program, I had to fundraise every dollar of our budget as we were totally donor-supported, with no institutional funds. All of our funders got it – they got the “story” of collegiate recovery, and they saw the success stories themselves in the experiences of our students and alumni. But some funders had questions: this is a good story and produces results, but is it the best way to produce those results? What are the dollars and cents here? And there were no answers in the literature. No one had crunched those numbers before. But it seemed pretty obvious to me – since I knew exactly how much our work cost – that it had to be a pretty darn good deal. I was pursuing my Master of Public Health part-time while working full-time as a director and happened to take a course on cost-effectiveness analysis. That led me to do a cost-effectiveness analysis of collegiate recovery programs for my master’s thesis, and I built my first cost-effectiveness calculator based on that analysis. The paper is in the Journal of American College Health, and the calculator is still in use and hosted on the Association of Recovery in Higher Education’s website. I liked doing direct services, but through this experience, I saw that I could indirectly impact my people on a much larger scale by making it easier for organizations doing this life-saving work to get the support and funding they need to do the work. So, I went into research full-time with the goal of closing some more of these gaps in the economic evaluation evidence base and making more of these tools.

Eric: Could you describe the PRSS cost-effectiveness calculator you recently created? To your knowledge, has this tool been adopted by organizations, and if so, what has been the feedback?

Dr. Castedo de Martell: We have had excellent feedback from organizations using the tool. It’s a calculator that gives you tailored results about the cost-effectiveness, averted societal and medical costs, and estimated impact of your PRSS-providing program. It also has a tab for bystander naloxone distribution. I’ve done dozens of webinars and talks about the calculator. At this point, people really seem to like it and want to be able to use it. It’s a pilot calculator I developed as part of my dissertation research with a pilot grant from the Recovery Research Institute, so that means that we absolutely have plans to fix it up, expand it, and incorporate feedback in the future. So please give us feedback! We developed it with the input of two Austin, Texas recovery care organizations (RCOs) – Communities for Recovery and RecoveryATX – but for future versions, we welcome as much feedback as possible as we want it to be as useful as possible to organizations doing this work. Organizations that have used the calculator and included results from the calculator into funder reports have gotten positive feedback from funders and continued funding – and that’s exactly the kind of impact I was hoping it would have!

Eric: PRSS has been demonstrated in the professional literature to have an impact on the total cost of care under a number of circumstances. From your vantage point, what has been your experience?

It isn’t rocket science to understand that if we only throw expensive, acute care at a chronic problem, then not only are we simply wasting money, we’re needlessly compounding human suffering, too.

Dr. Castedo de Martell: It isn’t rocket science to understand that if we only throw expensive, acute care at a chronic problem, then not only are we simply wasting money, we’re needlessly compounding human suffering, too. We, as a society, have understood that for decades for problems like heart disease. You cannot simply send someone home from the hospital after a heart attack with no follow-up plan, no medication, no anything. As a society, we accepted that a long time ago, yet for a long time, there had been blinders on much of our system with regard to addiction: expensive, acute treatment episodes and then good luck, at best. Now that’s not to discredit the good that acute treatment can provide, but it’s simply not enough. Informal peer support that has been flourishing across this country in various forms is also tremendously helpful, but it’s exactly that – informal, and it’s also simply not enough. The flourishing of more formalized peer recovery support services takes so many of those good aspects of the informal peer support community and formalizes it. There’s formalized training, there’s credentialing which means there’s accountability if someone is acting in a predatory way. Importantly, PRSS is a way for people for whom other career paths may be cut off due to criminal legal system involvement is now open to them – and that’s a tremendously important equity opportunity. So PRSS is tremendously important for a lot of reasons, but to answer your specific question, it saves a ton of money – not just to society, not just to the health care system, but to the individual getting services, too. It’s extending the continuum of care into low-intensity, long-term support delivered by credible messengers who have both training and lived expertise to navigate these incredibly challenging systems and help someone through this chronic disease long-term.

Eric: Looking into the future, how do you see PRSS contributing to a shift to value-based care and addiction payment reform?

Dr. Castedo de Martell: Many peer-driven organizations in the behavioral health space have a hard time doing the work they do within a fee-for-service reimbursement model. There’s a great study by Ostrow and colleagues from 2017 [i] that shows exactly that. As PRSS continues to expand and as greater swaths of the public and decision-makers see how it saves and transforms lives and does so very efficiently, then I think we’re going to see more folks come around to embracing the way that these organizations would prefer to deliver services. Human lives aren’t linear, addiction and recovery aren’t linear, and trying to dole out services in a very linear, fee-for-service fashion is just kind of a poor fit.

[i] DOI: 10.1007/s10488-015-0675-4

Human lives aren’t linear, addiction and recovery aren’t linear, and trying to dole out services in a very linear, fee-for-service fashion is just kind of a poor fit.

Eric: From your perspective, what have been some of the challenges with demonstrating the financial value of PRSS, and how have you navigated them?

Dr. Castedo de Martell: There’s one big challenge that is technical and one big challenge that is just inherent to PRSS. The one inherent to PRSS is that it’s meant to be flexible. That’s one of the fantastic things about PRSS. However, that also makes it hard to model and do any kind of economic evaluation – let alone all the challenges that other scientists have highlighted about just evaluation of PRSS outcomes in general. I have found it useful to think of PRSS as many different types of interventions. For instance, there’s PRSS as a short-term intervention for visiting someone who just experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose in the emergency department; there’s long-term recovery coaching, and so on. Even though it’s all PRSS, it’s really useful to chop them into discrete interventions for this kind of analysis. And I mean “intervention” in the public health sense – it’s just the general word we use for any kind of service, program, or activity that is meant to address some kind of health problem. The other problem is very technical. Many types of economic evaluation rely on something called a quality-adjusted life year. That’s basically just capturing the idea that an intervention adds years to your life, but it may have impacts on the quality of that life. Chemotherapy is an excellent example: it absolutely can save and extend lives for cancer patients, but it is universally regarded as incredibly unpleasant and really takes a toll on a person. Some ways of measuring quality of life can easily translate into estimating quality-adjusted life years. Unfortunately, for decades in recovery research, we have not been using measures that easily translate into quality-adjusted life years. We have mountains of quality-of-life data but we can’t easily use it in economic evaluation research for recovery-oriented interventions. I recently completed a project, funded by CHERISH, to help address this issue by developing a mapping algorithm for the quality of life measure that the SAMHSA GPRA uses, so that should hopefully help make it easier to use the mountain of data that can be used for estimating quality-adjusted life years in economic evaluations. I will be presenting those results in October at the Addiction Health Services Research Conference and will have a paper out in the coming months with those results.

Eric: What are some final considerations you would like to pass along to our Alliance participants?

Dr. Castedo de Martell: There are two things that the field of recovery research really needs right now. One is we really need more researchers who have lived experience with substance use disorder and who are willing to bring that experience to bear in their work and use it as the asset that it is. The second is that we really need more health economics researchers working in this space. If you’re already a health economics researcher, consider jumping into this field – we need all hands. If you’re considering a career in research, please consider developing some skills in economic evaluation because we really could use more of you!

Eric: Dr. Castedo de Martell, thank you for your work and the contribution your research has made to demonstrating the financial effectiveness of PRSS!

The Alliance for Addiction Payment Reform (Alliance) is a national multi-sector alliance of health care industry leaders – including payers, health systems, recovery service providers, and subject matter experts – dedicated to aligning incentives and establishing a structure that promotes the type of integration and patient care capable of producing improved outcomes for patients, payers, and health systems. The Alliance brings together clinical, addiction, information technology, primary care, social, regulatory, and policy expertise and has logged hundreds of hours of workgroup meetings, ratifying consensus principles and outputs.

Chestnut Health Systems is a 501c3 not-for-profit organization offering a comprehensive scope of behavioral health and human services in Illinois and Missouri. The research wing, the Lighthouse Institute, includes a team of 11 research scientists and 110 staff, including the NIDA-funded Justice and Emerging Adult Populations (JEAP) Initiative.